3 min read

May Housing Starts Plummet and Softwood Lumber Prices Follow

John Greene

:

Jun 23, 2022 12:00:00 AM

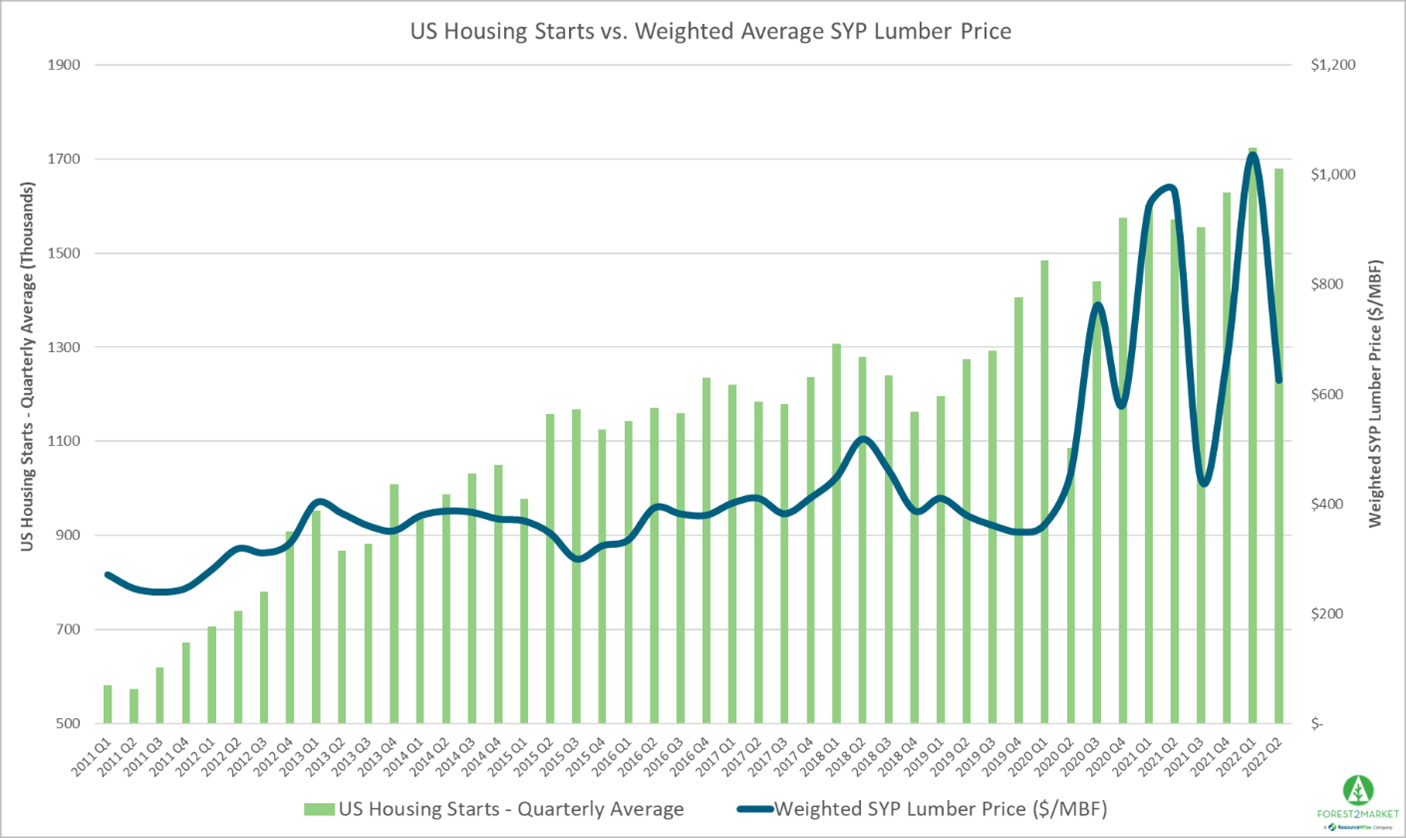

US homebuilding plummeted to a 13-month low in May, and prices for finished softwood lumber followed suit as the housing market cools amid surging mortgage rates and crippling inflation.

Housing Starts, Permits & Completions

Privately-owned housing starts decreased 14.4% in May to a SAAR of 1.549 million units. Single-family starts were down 9.2% to a rate of 1.051 million units and starts for the volatile multi-family segment plunged 26.8% to a rate of 469,000 units.

Privately-owned housing authorizations were down 7.0% to a rate of 1.695 million units in May, and single-family authorizations were off 5.5% to a pace of 1.048 million units. Privately-owned housing completions were up 9.1% to a SAAR of 1.465 million units. Per the US Census Bureau Report, seasonally-adjusted MoM total housing starts by region included:

- Northeast: +14.6%

- South: ‐20.7%

- Midwest: +1.9%

- West: ‐17.8%

Seasonally-adjusted MoM single-family housing starts by region included:

- Northeast: +5.5%

- South: ‐10.0%

- Midwest: ‐5.9%

- West: ‐11.8%

In early June, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate jumped to 5.99% – the highest level since 2008. Reflecting the sense of trepidation in the near term, he NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI) has now dropped six months in a row, hitting 67 in mid-June.

“Six consecutive monthly declines for the HMI is a clear sign of a slowing housing market in a high inflation, slow growth economic environment,” says NAHB Chairman Jerry Konter. “The entry-level market has been particularly affected by declines for housing affordability and builders are adopting a more cautious stance as demand softens with higher mortgage rates.”

Market Trends

The permits, starts, and sales statistics seem to suggest that the first bit of air is seeping out of the housing bubble. To the extent mortgage rates continue rising, potential buyers will find it correspondingly more difficult to afford a purchase unless home prices begin to retreat.

Interestingly, sellers do seem to be adjusting to the new reality — but for how long? Prices are prohibitive amid crippling inflation and surging interest rates:

- The median price for new homes in April was $450,600 (up 3.6% MoM). Moreover, 15% of new homes sold in April were priced at/above $750,000—more than double the year-earlier proportion.

- Existing home prices averaged $397,600 in May (up 14.8% MoM). Median single-family, three-bedroom home prices are rising faster than average wages in 92% of counties, Attom recently reported.

Taking a more detailed view of the dynamics at play across the housing market, May data from Realtor.com “…reveals a major turning point in inventory, with the count of home listings actively for sale growing compared to last year for the first time since mid-2019. Sellers are fueling this turnaround in inventory, with newly listed homes entering the market at a rate not seen since 2019. However, moderating demand is also playing a role, with pending listings declining compared to last year. Nonetheless, homes are still spending less time on the market compared to last year and prices are still rising, partially driven by an increase in newly listed larger homes and slow adjustments to seller expectations.”

Realtor.com highlighted some additional data that illustrate the tight conditions:

- "The national inventory of active listings increased by 8.0% over last year, while the total inventory of unsold homes, including pending listings, still declined by 3.9% due to a decline in pending inventory.

- The inventory of active listings was down 48.5% compared to May 2020 in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, there are still only half as many homes available.

- Housing remains expensive and fast-paced with the median asking price at a new high while time on market is at a new low."

In the near term, a modest amount of price relief may come from the 1.665 million (seasonally adjusted) housing units under construction; supply chain issues are the most likely reason for such a large volume of unfinished units. Nearly half (822,000) are single-family units — the highest level since 2006. Many of these homes are already sold, which means — per Bill McBride — it is unlikely this is “overbuilding” or that those units will significantly impact prices (although the buyers will be moving out of their current homes or apartments once these homes are completed). The other half (828,000) are multi-family units — the highest level since 1974.

Declining softwood lumber prices should also offer some relief, as prices have been plummeting since late February. In mid-June, Forest2Market’s composite southern yellow pine lumber price had dropped 60% from a 2022 high achieved in early March.

As we recently wrote in our coverage of the dynamic lumber market, a high degree of uncertainty continues to plague lumber producers in a business climate still dominated by inflation, stressed supply chains and shifting geopolitical dynamics. There are two related questions/concerns about the near-term performance of North American lumber prices:

- Is the market becoming overproduced?

- What happens when demand falls off for a more prolonged period of time?

Lumber prices are already seeking a new floor and with more technology-driven, low-cost production coming online, a glut of lumber (or shrinking demand) will drive high-cost producers out of the market. Any prolonged softness in new homebuilding will then stimulate a rebalancing of the market, which will force those remaining producers to adjust production and remove excess supply.

As illustrated in the chart above, lumber producers have been stuck in a vicious cycle of chasing a moving target while delicately balancing inventories and costs for over two years. This is especially difficult for manufacturers to manage since 1) economic conditions continue to become more precarious, and 2) there is little surge capacity in the supply chain - historically, the market does not allow it. And now, the FED is more aggressively tinkering with reactionary measures to drive desired outcomes across the broader economy. However, this is the type of meddling that could keep the housing and lumber markets stuck in a mismatched cycle for the foreseeable future.

![[Video] Molecules to Markets Episode 1: Chemical Markets Begin 2026 in a Supply-Driven, Margin-Sensitive Environment](https://www.resourcewise.com/hubfs/images-and-graphics/blog/chemicals/2026/weekly-video-series-molecules-to-markets/CHEM-Weekly-Video-Series-Molecules-to-Markets-Episode-1.png)