3 min read

Wood Fiber Supply Chronicles, Part 1: Divestment, Depression and Demand Create Bio-mess

Pete Stewart

:

January 22, 2015

Pete Stewart

:

January 22, 2015

In this series, I will discuss the difficult circumstances that consumers of wood fiber are facing. In this first post of the series, the focus will be on the events that have created restricted wood supply and that will likely plague the industry for years to come:

- The unintended consequences of timberland divestment

- Bad luck in the timing and intensity of the housing bust

- Inattention to—and an inability to react to—global policy changes

Factor 1: Unintended Consequences

Starting in the late 1980s, a trend toward separating mills and the timberlands they owned began taking shape. This de-integration of forest products companies, largely driven by Wall Street as a cure for low returns, moved through the industry like a cold virus moves through the second grade, picking up steam in the mid-1990s and crescendoing in 2006. Over a 15-year period from 1995 to 2010, nearly 25 million acres of US timberland changed ownership. While the divestiture of timberlands did not help or hurt paper stock returns, it did provide capital to fund industry consolidation that, in turn, dramatically improved pulp and paper company returns.

This trend also had unintended consequences, however. The new owners of the trees—mostly professional investment managers—have different ideas about how to manage timberland. They care little about growing pulpwood, favoring longer sawtimber rotations that produce higher returns instead. This simple change in management objectives has effectively taken 30 million tons of supply out of the system annually.

Factor 2: Bad Luck

Following quickly on the heels of these divestitures, the industry experienced a run of bad luck in the form of the housing bust. Factor 1 (unintended consequences), coupled with the depressed housing market, delayed final harvests and subsequent replantings.

Final harvests play an important role in the southern pine plantation model. They supply the logs used to make lumber, and they make land available for future tree plantings. During the housing downturn, final harvests were reduced by 32%. New plantings were reduced by roughly the same amount as a result. All the while, pulp/paper demand (except for a short period after the financial crash) hummed along unencumbered. And as sawmills struggled to produce half the traditional volume of wood chips, demand for pulpwood stumpage increased. Most of this increase was sourced from thinnings and rethinnings.

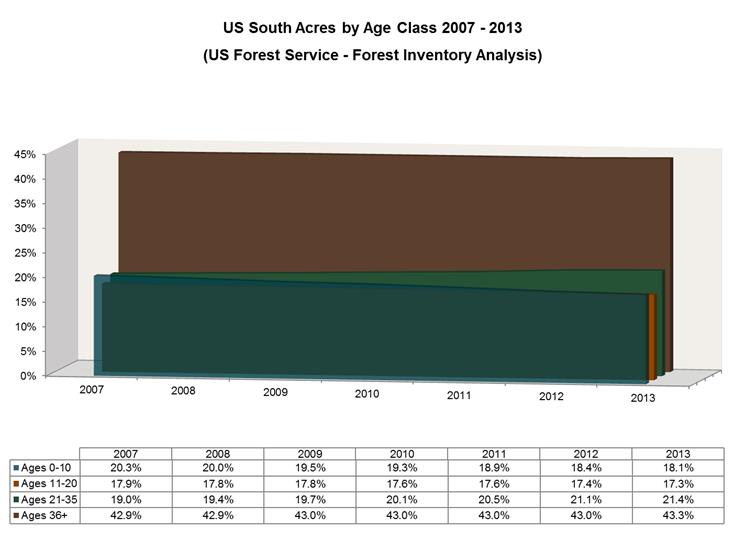

No one predicted the extent of the housing bust and the following great recession. In hindsight, however, these economic events were more than a bit of bad luck for the southern wood supply (Read Timber Supply and Demand Trends Confirmed by FIA Data). The ramifications will play out for some years to come. The following chart shows the result of the slack replantings and excessive thinnings: a skewed age class distribution where the number of small trees (future volume) is decreasing and the number of old trees is increasing. Much reduced replanting means reduced future growth.

Factor 3: New Demand

Meanwhile—and likely at the worst time possible—new demand from wood pellet consumers in Europe was introduced into the market. A nascent pellet industry secured a foothold in 2007, then grew in fits and starts until 2010. When it was clear that UK and European support subsidies were solidly in place, industry growth accelerated. In 2014, this highly subsidized industry used 10 million tons of wood fiber. The upshot here is that the pellet industry is subsidized by European governments and taxpayers, two groups not easily influenced or even understood by the US pulp and paper industry.

The nexus of these three factors—unintended consequences, bad luck and European pellet demand—is a pretty hefty price tag: they have cost the US South pulp/paper industry approximately $1 billion by our count.

Now, I am not suggesting that these dollars vanished, but rather they were redistributed to wood suppliers and timberland landowners. And that is certainly true. But it is also true that continued fiber price escalation will threaten the US South’s global pulp cost position.

When I began my career in the early 1990s, pine pulpwood stumpage was selling for around $8 a ton. Today, 23 years later, pine pulpwood on average sells for about $12, hardly keeping pace with inflation. But in the early 1990s, the US pulp producer was not competing with new pulp mills in China, Indonesia, Chile and Brazil – all of whom can now produce pulp at a lower cost than producers here at home.

The pellet industry is being singled out as the culprit of the escalating price of wood fiber. And that is partially correct. However, as noted earlier, the consequence of separating the timberland from the mill owner backfired (Strike 1). Second, the pulp/paper industry underestimated the resolve of the European governments to subsidize bioenergy in the form of pellets. When it was clear that the pellet industry had a foothold, any window of opportunity to do something about it had closed (Strike 2).

To understand their resolve (and to realize we’re not in Kansas anymore), one only has to eat at a café in Denmark or ride in a taxi in the Netherlands and read a proudly displayed sign in either that says “we offset our carbon footprint by….” Quite simply, the rules by which we play don’t apply. While the industry rails against government subsidies that lead to unfair competition, the average EU citizen revels in the fact that they are saving the planet. While we focus on free and fair trade, EU member states go about subsidizing bioenergy. While we aim at the wrong target by lobbying our Congress, EU member parliaments pass laws that affect the US supply chain.

Over the course of this series, I will delve into these issues—both their causes and consequences—and suggest some course corrections and bold ideas for working ourselves out of these highly fractured circumstances before a “change up” that we can’t handle crosses the plate.

Read 10 Predictions for Wood Consuming Industries in 2015 for more developing trends.