5 min read

Will the Affordable Clean Energy Rule Save a Spot for Biomass?

John Greene

:

December 6, 2018

In early October 2018, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt announced the formal process to repeal the Clean Power Plan—essentially limiting any tangible prospects for the near-term expanded use of biomass use in the US. In the wake of this news, however, the Agency (EPA) proposed a “replacement” rule with the aim of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from existing coal-fired electric utility generating units and power plants across the country. This new proposal, entitled the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule, establishes emission guidelines for states to use when developing plans to limit GHGs at their power plants and, in the EPA’s own words, “empowers states, promotes energy independence, and facilitates economic growth and job creation.”

While the CPP’s goals were ambitious, the Plan’s critics were concerned about federal overreach; many believed that it exceeded the EPA’s authority, which is why 27 states, 24 trade associations, 37 rural electric co-ops, and three labor unions challenged the Plan, and the Supreme Court issued an unprecedented stay of the rule.

The ACE proposal’s comment period ended on October 30. If enacted, the Rule would work to reduce GHG emissions through four main actions:

- ACE defines the “best system of emission reduction” (BSER) for existing power plants as on-site, heat-rate efficiency improvements.

- ACE provides states with a list of “candidate technologies” that can be used to establish standards of performance and be incorporated into their state plans.

- ACE updates the New Source Review (NSR) permitting program to further encourage efficiency improvements at existing power plants.

- ACE aligns regulations under CAA section 111(d) to give states adequate time and flexibility to develop their state plans.

In addressing the change in tone from Washington in combination with a new plan, EPA Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler said “The ACE Rule would restore the rule of law and empower states to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and provide modern, reliable, and affordable energy for all Americans. Today’s proposal provides the states and regulated community the certainty they need to continue environmental progress while fulfilling President Trump’s goal of energy dominance.”

EPA’s regulatory impact analysis (RIA) for this proposal includes a variety of scenarios based on the central point of the statute: to give states the flexibility needed to consider when it comes to standards of performance. Key findings include the following:

- EPA projects that replacing the CPP with the proposal could provide $400 million in annual net benefits.

- The ACE Rule would reduce the compliance burden by up to $400 million per year when compared to CPP.

- All four scenarios find that the proposal will reduce CO2 emissions from their current level.

- EPA estimates that the ACE Rule could reduce 2030 CO2 emissions by up to 1.5% from projected levels without the CPP – the equivalent of taking 5.3 million cars off the road. Further, these illustrative scenarios suggest that when states have fully implemented the proposal, U.S. power sector CO2 emissions could be 33% to 34% below 2005 levels, higher than the projected CO2 emissions reductions from the CPP.

Current state of Biomass in the US

While the ACE aims to transfer more control to the state level, the only drivers in place now are the individual 35 state Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS). These systems allow lots of flexibility and, therefore, most capacity increases in electricity generation in the US market are driven by economics; natural gas (due to the current low cost and high availability) is the current default fossil energy source of choice while solar PV is the current renewable technology of choice.

Biomass fuels provided roughly 5% of total primary energy use in the US in 2017. Of that 5%, about 47% was from biofuels (primarily ethanol), 44% was from wood and wood-based biomass, and 10% was from municipal waste (the sum of percentages is greater than 100% because of independent rounding) So, in 2017, about 2% of total US annual energy consumption was from wood raw materials—biomass sources that include bark, sawdust, wood chips, wood scrap and mill residues.

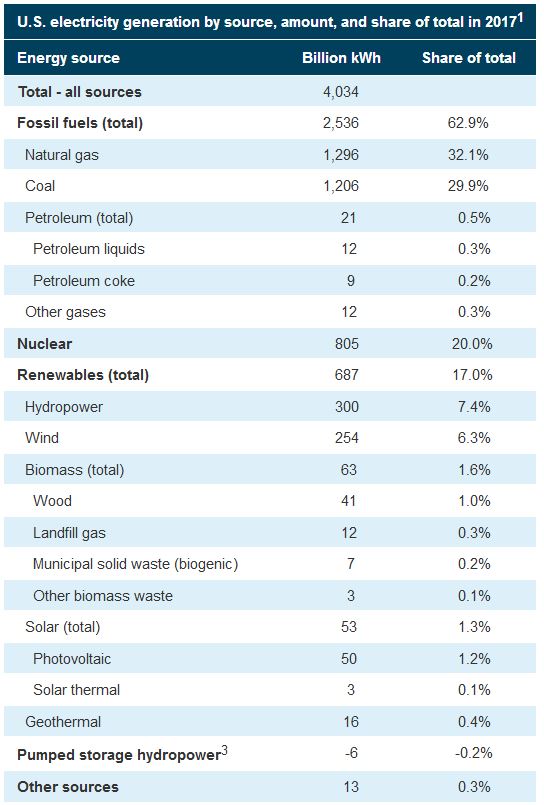

Drilling down into electricity production specifically, roughly 4,034 billion kilowatthours (kWh) of electricity were generated at utility-scale facilities in the US in 2017. About 63% of this electricity generation was from fossil fuels (coal, natural gas, petroleum, etc.); 20% was from nuclear energy, and about 17% was from renewable energy sources—a vast majority of which was generated by wind and hydropower. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that an additional 24 billion kWh of electricity generation was from small-scale solar photovoltaic systems in 2017.

The amounts (in trillion British thermal units) of US wood and wood waste energy consumption by consuming sector and their shares (percent) of total wood and wood waste energy consumption in 2017 are detailed below. As you can see, most of this wood waste is used at the industrial level primarily by wood products manufacturers; only 12% of the BTU consumption was for electricity generation.

- Industrial: 1,480 BTU, 69%

- Residential: 334 BTU, 16%

- Electric power: 247 BTU, 12%

- Commercial: 84 BTU, 4%

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

In 2017, there were a total of 178 operational biomass power plants utilizing some form of wood-based feedstock (65 of them used municipal waste) in the US. However, in areas of the country that have an existing biomass infrastructure and supply chain in place—like the Northeast—biomass continues to face both market and legislative hurdles.

- In New England, one-fifth to one-third of the total volume of timber harvested annually is used as biomass. As other markets for low-grade wood (notably pulp mills) have been reduced or disappeared altogether, the biomass market has become increasingly important for loggers and landowners. As a renewable resource that requires the constant purchase of new fuel, biomass provides ongoing economic impacts to the forest supply chain (and beyond) that other renewables like wind and solar do not.

- Recognizing the important role biomass plants play in the forest economy, northeastern states have been acting to support continued operations. Last year, Maine allocated nearly $14 million to support continued operations at four biomass plants, attempting to close the gap between operating costs and fuel costs. This year, it was New Hampshire’s turn. The state has six “legacy” biomass plants—all under 20 megawatts in capacity—that were built decades ago. Just last month, the New Hampshire Legislature overrode a veto by Gov. Chris Sununu that will require utilities to purchase a portion of their electricity from the state’s wood-burning power plants. However, these plants are likely on borrowed time.

What does the ACE Rule Mean for Biomass?

In its analysis of the proposed Rule, environmental litigation firm Beveridge & Diamond wrote that, “EPA proposes not to include co-firing of natural gas or biomass as components of BSER. EPA contends that ‘regional considerations and characteristics (e.g., access to biomass, or natural gas pipeline infrastructure limitations)’ prevent co-firing from being a national-level solution. For example, natural gas ‘cannot be stored in quantities sufficient for sustained utilization on site,’ and biomass is subject to ‘regional supply and demand dynamics.’ Moreover, co-firing methods ‘have been shown to be costly.’ EPA proposes to include co-firing as a compliance option that states may consider and solicits comment on whether to include co-firing among the list of BSER candidate technologies.”

Beveridge & Diamond continues, “At the same time, the proposed ACE Rule notably references EPA’s April 23, 2018 announcement stating that EPA will ‘treat biogenic CO2 emissions resulting from the combustion of biomass from managed forests at stationary sources for energy production as carbon neutral.’ Based on this statement and the inclusion of co-firing in the CPP, many groups are likely to argue during comments and litigation that co-firing is an ‘inside the fence line’ measure that is adequately demonstrated and more widely deployed than several of the HRI ‘candidate technologies’ EPA’s proposal would recognize as BSER.

Like most comprehensive environmental legislation, the road towards enacting some form of the proposed ACE Rule will be a long one, no doubt fraught with intense litigation. Several environmental groups and state attorneys general have already threatened to challenge any final ACE Rule. Beveridge & Diamond concludes: “And with the regulatory and litigation processes likely to extend into the next administration, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether the ACE Rule will survive or serve merely as the next iteration in EPA’s ongoing saga to establish GHG standards for existing power plants.”