If you can’t move chips, you can’t make lumber. Sometimes we forget that when a sawmill buys logs (cylinders) and sells lumber (rectangles), everything that didn’t become a board has to go somewhere. While mills have spent significantly on technology to reduce residues, there simply isn’t a way to stop sawmills from turning out chips, sawdust and bark.

Every mill is unique, but a decent rule of thumb is for every thousand board feet of lumber produced, two tons of residues are produced—one ton of clean chips, and another ton of bark and sawdust. Precise statistics are hard to come by, but New England sawmills produce somewhere on the high side of 1.3 billion board feet of lumber annually. Region-wide, about two-thirds of the production is softwood—spruce, fir, white pine and hemlock. Maine is responsible for the lion’s share of this production, but New Hampshire and Vermont check in with respectable production, and all states in the region have sawmills.

Assuming that the production of a thousand board feet of lumber results in residues equal to a ton of clean chips, 1.3 billion board feet of lumber means that there are 1.3 million tons of chips that need to find a home. In order for a sawmill to keep turning logs into lumber, the mill residue has to go somewhere—typically a pulp mill, a wood pellet mill, a biomass power plant, a local school with a chip boiler, or it may be used on-site for energy production.

Since the beginning of 2014, Maine has lost over 4 million tons of low grade market—most of which were pulps mills(which use mill chips), with some biomass market loss as well. While pulp mills in the state still use somewhere around 7 million tons of wood annually (pulpwood and mill chips), softwood has taken a huge hit. Over 1.5 million tons of softwood market have vanished in the past few years. Shuttered pulp and paper mills in Bucksport, East Millinocket, Lincoln, and Madison were all softwood consumers, and are now gone. Other pulp mills have cut back production levels.

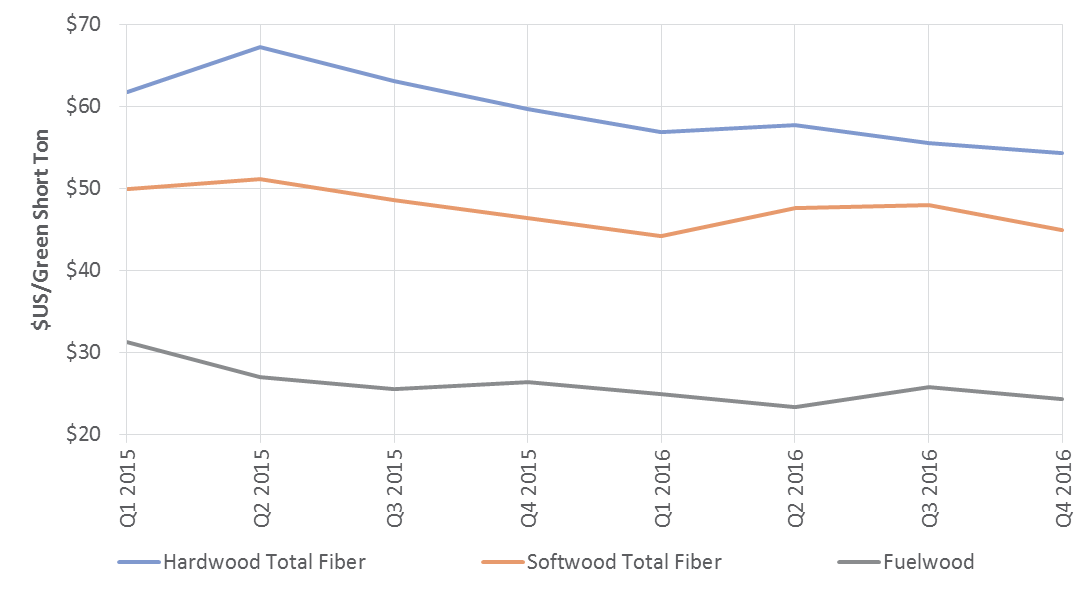

Forest2Market benchmark data confirms this trend. As evidenced in the two charts below, product categories that make up the residuals market have all decreased in price since Q12015 despite a few temporary spikes along the way. Hardwood total fiber has dropped 13 percent, softwood total fiber is down 10 percent and fuelwood has been hit the hardest with a 23 decrease in price.

In addition to pulp mill markets lost, many of the remaining markets aren’t exactly on firm footing. Biomass power plants in the region are struggling with (relatively) low wholesale electricity prices, as well as renewable energy certificate (REC) prices that have lost half their value since 2015. Two biomass plants reopened and two more were given a lifeline with $13 million in funding from Maine, but that provides only a temporary reprieve. The region’s pellet mills—which in this region sell to homeowners and businesses for heating—are competing against lower heating oil prices and still recovering from a very warm winter last year and sluggish sales this winter.

Those sawmills that rely upon pulp, biomass and pellet markets to operate are growing increasingly concerned. Forward thinking sawmills are developing options to make certain they have an outlet for their residue. One white pine mill is installing a small pellet mill to handle their chips and sawdust, and other mills are evaluating this same strategy. Another sawmill is in the process of building a new combined heat and power system (CHP); they plan on purchasing biomass fuel from local loggers and using the system as an outlet for mill chips if necessary.

Sawmills are critical to the success of the entire forest products industry in the Northeast (and every other region as well). In Maine, which has long been thought of as a “pulpwood state,” the most recent figures from the state’s Forest Service suggest that sawlogs represent about a quarter of the volume harvested, but two-thirds of the stumpage paid to landowners. Sawlogs are even more important to landowners in other parts of the region. For decades, a wide range of markets for mill residues helped support the continued health of that sector, and provided the region with a competitive advantage. Those days are gone. Today, sawmills (and the entire forest products industry) in the Northeast need to pay careful attention to moving residues as efficiently as possible in order to assure their continued operations and profitability.