3 min read

Labor Challenges Part 1: Where Have America’s Workers Gone?

John Greene

:

December 9, 2021

Over the last 20 years, the US population has grown by roughly 17% as a result of adding over 50 million new inhabitants. For scale, that’s equivalent to adding the entire population of South Korea — which is no small feat — over the course of just two decades.

But looking at employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics over the same time period, one might assume that the population in the US is drastically shrinking. For instance, notice the rapidly decreasing trend in the labor force participation rate (LFPR) dating back to 2000 in the graph below. Even after the temporary plunge during the Great Recession in 2008, workforce participation trended down, bottomed in 2015, and thereafter made just modest gains before falling off a cliff at the onset of the pandemic.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Which begs the obvious question: If the US added 50 million people since 2000, how has the LFPR declined by 7%? Where did millions of workers go?

Recent Trends

In October, the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) establishment survey showed non-farm employers adding a “solid” 531,000 jobs – far better than the 450,000 expected. Goods-producing industries gained a respectable 108,000 jobs; service-providers: +423,000. Job growth was widespread, with notable gains occurring across sectors:

- Leisure and hospitality: +164,000

- Professional and business services: +100,000

- Manufacturing: +60,000

- Transportation and warehousing: +54,400

The October labor force participation rate was unchanged at 61.6% since the expansion of the civilian labor force in October only partly recouped September’s shrinkage of 183,000; also, the number of employment-age persons not in the labor force rose modestly (+38,000) to 100.5 million.

“Despite widely reported worker shortages, strong underlying demand in the economy is steadily healing the labor market,” BMO Capital Markets’ Sal Guatieri wrote. “The only thing missing now is an upturn in participation as the market tightens and wages rise further.”

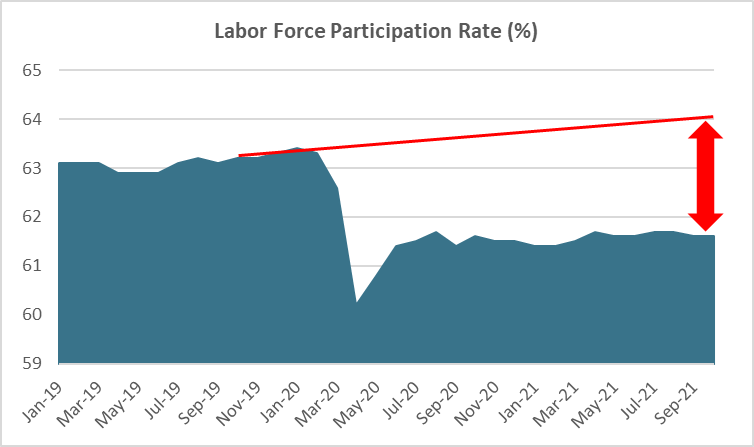

In the graph below, notice labor force participation was slowly trending up in 1Q2020 before abruptly freefalling when the pandemic lockdowns took widespread effect last April. Some percentage of the displaced employees came back to work by mid-summer, but a sizable chunk has remained on the sidelines. Which begs another obvious question: Since the onset of the pandemic in the US, where did an additional 3 million workers go?

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

A Perfect Storm

Some of the estimated 3 million “excess” workers who disappeared during the pandemic might return to work if conditions become sufficiently attractive, although it is possible that the various vaccine mandates being imposed around the country have discouraged some from returning to the workforce at all. However, the OSHA-driven Emergency Temporary Standard (ETS) mandate has been halted after the Fifth Circuit Court issued a preliminary stay of the law’s implementation.

More pointedly, wages for US workers have grown very slowly over the last several decades and, for much of 2021, rampant inflation has been chipping away at American paychecks even more. With the consumer price index (CPI) running at an annual rate of +5.4% in September, even those who are employed are—on average—losing significant purchasing power.

- The cost of rent jumped 0.5% in September, marking the biggest increase in 20 years.

- The index for food rose 0.9%; grocery prices have climbed 4.5% in the past year and are increasing three times faster than they did in the five years before the pandemic.

- The energy index increased 1.3%, with the gasoline index rising 1.2%.

And there doesn’t appear to be any end in sight. Whereas Fed Chair Jerome Powell has insisted for months the surge in inflation was temporary—and largely reflecting a rise in pent-up demand after the economy fully reopened—Atlanta Fed Bank President Raphael Bostic recently said 2021’s sharp increase in prices has broadened beyond just a handful of major goods such as autos and lumber and “will not be brief.” Bostic said he and his staff will no longer refer to inflation as “transitory” because the current inflation could persist for quite a while, perhaps well into 2022 and beyond.

Per Bloomberg, Powell now appears to be changing his tune: “The temptation at the beginning of the recovery was to look at the data in February of 2020 and say, ‘Well, that’s the goal because that’s what we knew’ — we knew that as achievable in a context of low inflation. There’s room for a whole lot of humility here as we try to think about what maximum employment would be. ... We have a completely different situation now where we have high inflation, and we have to balance that with what’s going on in the employment market.”

Powell then acknowledged that “the level of inflation we have right now is not at all consistent with price stability.” Clearly, runaway inflation in combination with a flagging LFPR is not a sustainable model. But if employers and potential employees are now engaged in a prolonged game of “chicken,” something has to give… and inflationary pressures are likely to accelerate the pace of the game.

Are millions of workers poised to come back to work in 2022? Or is the “Great Resignation” a structural change that will have cascading impacts for employers over the next decade? We’ll take a closer look at potential outcomes in the second installment on this topic.