Let’s take a trip down memory lane to the early 1990s. Greed was good, computers sat on desktops, cell phones were the size of bricks, Seattle’s grunge scene was just breaking, and the paper industry thought it was a growth business. They were heady days indeed, and like any good party or business cycle, no one could see the writing on the wall: the party couldn’t go on forever and, ironically, the behavior itself was ultimately setting the scene for an inevitable collapse.

Greed is still greed (we can’t eliminate an original sin), grunge dissolved while cell phones and computers evolved, but paper as a growth industry? That’s crazy talk you say!

But think of it this way: at the time, newspaper circulation was still growing with predictable and positive bumps in election and Olympic years, as was uncoated freesheet as individuals bought new-fangled printers for their personal computers. Sure, plastic was making inroads on many packaging grades but for the printing and writing set, the future was so bright they had to wear shades. And from a Wall Street perspective, many publicly traded paper companies were committing sins far more egregious than greed - they were blowing shareholder’s equity on new capacity.

Wall Street has both an incredibly long memory and a tendency for holding a grudge, so the excesses of the paper industry late in the 20th century were a huge cross to bear for the first decade of the new millennium. But in the last decade, there have been a few major investments by industry leaders in various grades. So, is Wall Street getting soft when Environmental, Social & Corporate Governance (ESG) goals have supplanted pure profits as the de facto corporate agenda, and new capacity isn’t necessarily a four-letter word? Can paper companies deploy capital without destroying shareholder value? Is this time really different?

The last question is of course a trick, as any investor knows that an affirmative answer will lead to highly negative consequences. However, that doesn’t imply that a more nuanced examination of the business backdrop won’t lead to a different reason for deploying capital. In a “capital intensive” industry like pulp & paper, companies must constantly repair and replace parts simply to continue operations and maintain safety. Generally, companies spend less than deprecation and return the excess capital to shareholders, but sometimes bigger ticket items are needed. The key determinant of the success of large investments will always be the impact on supply/demand and, ultimately, profitability. However, profitability and value creation are increasingly a function of cost structure and market perception related to ESG initiatives.

The last question is of course a trick, as any investor knows that an affirmative answer will lead to highly negative consequences. However, that doesn’t imply that a more nuanced examination of the business backdrop won’t lead to a different reason for deploying capital. In a “capital intensive” industry like pulp & paper, companies must constantly repair and replace parts simply to continue operations and maintain safety. Generally, companies spend less than deprecation and return the excess capital to shareholders, but sometimes bigger ticket items are needed. The key determinant of the success of large investments will always be the impact on supply/demand and, ultimately, profitability. However, profitability and value creation are increasingly a function of cost structure and market perception related to ESG initiatives.

If you ever hear an investment pitch suggesting that “this time is different,” run don’t walk away!

In this second installment on the importance of ESG for modern companies, it’s important to differentiate between destructive and constructive capital investment. Our general conclusion for the mature P&P industry is that investment that adds capacity will not only be negatively viewed by the investment community, but it will often lead to negative outcomes for the sponsor. Conversely, capital that materially lowers costs and provides environmental benefits without increasing capacity can be extremely successful. We will examine two major investments below that support this conclusion.

Saving the best for last, we’ll start with the example of capital spending gone wrong. In this case, we refer to Rayonier Advanced Materials’ (Rayonier at the time) 2011 decision to expand capacity to its specialty cellulose (CS) facility in Jessup, Georgia. At the time, Rayonier was sold out, specialty cellulose prices were rising, and the company announced its intention to invest better than $300 million to convert the 230,000-ton C-line (fluff pulp) to produce 190,000 tons of specialty cellulose. The CS market at the time was comprised of 1.45 million annual tons, therefore the incremental capacity represented approximately 13% to a market that was growing in low single digit percentages annually.

The “Field of Dreams Strategy” (If you build it, they will come) might have worked for Steve Jobs,

The “Field of Dreams Strategy” (If you build it, they will come) might have worked for Steve Jobs,

but it’s not very successful in commodity industries.

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then the chart above with Rayonier Advanced Materials (RYAM) in red tells the story. The parent company – Rayonier – in blue didn’t fare too badly, and part of the negative performance in 2014 was the impact of the spinoff of RYAM. For Rayonier Advanced, the poor stock performance is attributable in part to its post-spin capital structure and the market’s lack of interest in a “small cap orphan,” but the bottom line is the Jessup capacity expansion, which came online in late 2013, shifted the market dynamic for specialty cellulose from tight to oversupplied, hence crushing prices and profits. And to make matters worse, RYAM tried to undo the damage and tighten specialty cellulose markets by converting the C-Line back to fluff (and restructuring its entire system), but the market (Wall St. and Main St.) never believed the excess capacity was permanently removed, and equilibrium has not recovered nearly a decade after the fateful expansion.

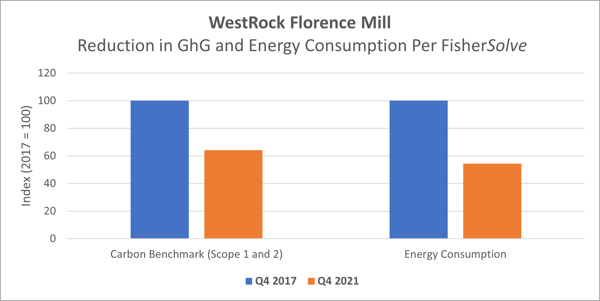

Recently, we have seen a couple of capacity-neutral investments that have had significantly less impact than RYAM’s double digit expansion at Jessup. WestRock’s big new machine at Florence, SC was capacity neutral with favorable economics for its sponsor. The project’s specific benefits to WestRock were clear, but the overall financial benefits are tough to isolate due to the size of the overall containerboard market and WRK’s product mix. That said, by consolidating production from three machines to one the Florence mill’s cost structure moved into the first quartile in North America. Moreover, the mill’s Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions are substantially reduced, as the FisherSolve benchmarks below illustrate. This could translate to further benefits as global brands increase their push for improvements in the “E” in ESG.

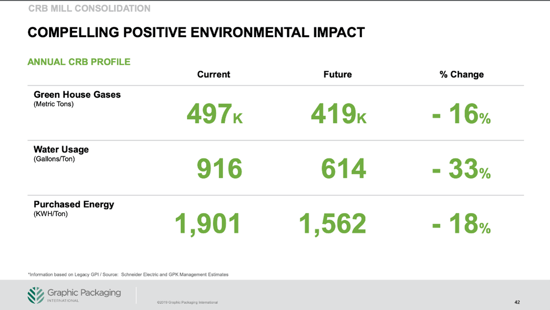

The most recent large investment is Graphic Packaging’s new 500,000-ton machine at Kalamazoo, Michigan in the highly consolidated coated recycled board (CRB) market. From the outset, GPK stressed that its $600 million project (announced in 2019 and scheduled for full ramp up this year), was capacity-neutral but anticipated to be highly accretive by consolidating GPK’s CRB system from 5 to 3 mills and reducing fixed and variable costs by $100 million annually. To be clear, GPK never suggested they were investing to satisfy future growth (although plausibly they could have, as paper-based packaging has a good environmental story compared to plastic) but were instead focused on the benefits of bringing down costs through lower fixed (four machines removed, two mills closed) and variable – fiber, energy, chemical, and other – costs.

Spending to bring down costs can be a compelling investment, particularly in an older, multi-mill system.

It is worth noting that when we rate these projects “win, lose or draw,” we are using perhaps the most one-dimensional measurement metric we can think of: Share price performance. When GPK announced the Kalamazoo strategy in 2019, they were sure to focus on the numbers the finance community would pay attention to – Net Capacity Change, $100 million annual savings on $600 million investment, and a 12% Internal Rate of Return. But they also put in some numbers that only three years later appear to resonate with Wall Street in a different way – those pertaining to the “E” in ESG.

We’ll give GPK management credit for seeing where the puck was going – the Kalamazoo project was featured in the Wall Street Journal (Jan. 2, 2022). While time will tell if the project is as financially successful as planned – GPK looks like they were ahead of the curve on the non-financial metrics – and if emissions like greenhouse gases (GHG) and other effluents are ever explicitly taxed at the “tail pipe,” this project could be a home run.

Graphic Packaging’s 2019 Investor Day featured a 51-page slide deck articulating Market Conditions, Strategy, Financial Objectives and the merits of the $600 million project at Kalamazoo. Not once was the term ESG used.

After analyzing these two case studies, it’s worth questioning why the investment community makes such a big distinction between adding capacity and spending capital to bring down costs. Its rather simple, really: When a market is in equilibrium - supply and demand evenly matched - a shift in either curve can have a dramatic impact on prices. We believe GPK concluded it was risky to add significant capacity to a market (CRB) that was growing at perhaps 1% (to be charitable), but they had an opportunity to revamp their system with a compelling project that will put their costs $130/ton below much of the competition.

It might not be fair to judge projects and the wisdom of their sponsors (management teams) solely on financial returns and ultimately share price, but the bottom line is that is still how the game is played and success is measured.

Getting back to the history lesson discussed in the initial paragraph, perhaps the 90s weren’t so important at all. The greatest period was clearly the 1960s when music was analog and famed economist Milton Friedman suggested that the “Social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.”

There are those who now take shots at both the 60s and Milton Friedman but again, if one allows for evolution, then maximizing profits and value requires “buy in” into socially responsible factors like ESG. With this in mind, significant capital spending decisions will have a laser focus on market impact (“do no harm”), cost position, and the quadruple bottom line of profitability and success on meaningful ESG benchmarks.