.jpg)

Since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in August, Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) has gained a lot of attention – especially as Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) metrics continue to influence global investment decision making. But what exactly is SAF, and what role will wood biomass play in the development of these innovative new fuels and the trend towards decarbonizing global industry?

SAF is a broad-based segment of biofuels used to power aircraft that has similar properties to conventional jet fuel, but with a smaller carbon footprint. Depending on the feedstock and technologies used to produce it, SAF can reduce lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions dramatically compared to conventional jet fuel. SAF’s lower carbon intensity therefore makes it an important solution for reduc.jpg?width=300&name=pexels-sam-willis-1154619(2).jpg) ing GHGs for two important reasons:

ing GHGs for two important reasons:

- Aviation GHGs make up roughly 8% of US transportation GHG emissions, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- Aviation is a segment that is under specific scrutiny, as its impact is extremely intensive for the product sold: 1% of the planet’s population emit 50% of total aviation GHG.

Despite its carbon intensity, SAF was not in the EPAct of 2005 or the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007. Why? The short answer is that the aviation fuels industry is just half the size of the diesel industry. To put this fuel segment into perspective, the US annually uses:

- 123 billion gallons of gasoline (and 15 billion gallons of ethanol used to blend)

- 64 billion gallons of diesel

- 23 billion gallons of aviation fuel

- 4 billion gallons of biodiesel/renewable diesel

Historically, aviation fuels never came under the low sulfur rules that impacted the diesel industry - much like the heating oil and other niche fuel markets. However, the Biden Administration issued a “Grand Challenge” in 2020 of incorporating 3 billion gallons of SAF into the aviation fuel mix by 2030

It’s an ambitious target since there are currently only 300 million gallons of SAF used worldwide. Assuming the US and DOD reach demand for 27 billion gallons of jet fuel by 2030 and need 3 billion gallons of SAF to meet Biden’s challenge, hitting the target by 2030 would require a 10-fold increase in SAF production, never mind the future global requirements of the industry.

Potential for SAF

The most noteworthy recent development for Sustainable Aviation Fuels is that the IRA allows for an income tax credit for blending SAF into regular jet fuels in US airports, which enables airlines to claim tax credits parallel to the other road transportation fuel companies, users, and blenders of fuels.

To achieve this, the bill includes two important incentives for SAF producers:

- The first is a $1.25 per-gallon credit available for each gallon of SAF sold as part of a qualified fuel mixture if the SAF has a demonstrated lifecycle GHG reduction of at least 50% compared to conventional jet fuel. The credit increases to a maximum of $1.75 per gallon in one cent per-gallon increments based upon the performance of the feedstocks and processing towards lowering the Carbon Intensity (CI) of the fuel.

- The second, which begins in 2025, is a tax credit for producers of general low-carbon fuels that can be used in aviation. This credit also will offer a $1.75 a gallon rebate for a 100% emissions reduction compared with fossil fuels.

However, there’s a catch: The first credit will be available in 2023 and expires at the end of 2024, and the fuel must be produced in the USA and not imported. The second credit starts in 2025 and expires at the end of 2027 – not exactly much time to get a successful project off the ground.

We can only speculate as to what policy may be in the future, but the purpose of the IRA is to support industry scaling to bring down production costs: low-carbon SAF is 2-4X that of conventional jet fuels. From an ESG strategy, the IRA provides the aviation sector with some level of incentive and an opportunity to begin “decarbonizing” the industry with SAF. In this light, it is an incremental step in the right direction.

What Role Will Biomass Play?

An estimated 1 billion dry tons of biomass can be collected sustainably each year in the United States; enough to produce 50–60 billion gallons of low-carbon biofuels. These resources include corn grain, algae, other fats, oils, and greases, agricultural residues, as well as forestry residues and wood mill waste.

Forest biomass is different than agricultural waste. Both agriculture and forest biomass were originally expected to contribute to cellulosic biofuels but in practice, the Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and RFS-2 built a framework for qualification that was designed to disincentivize the removal of forest resources from public lands and ecologically sensitive areas. The US produces corn on about 90 million acres/year, which generates 3-4 tons/acre of corn stover (waste). However, forest biomass can be harvested from roughly 300 million acres with 1-2 tons/acre of residue material. In other words, there are no major EPA restrictions on stover, while there are major restrictions on wood biomass.

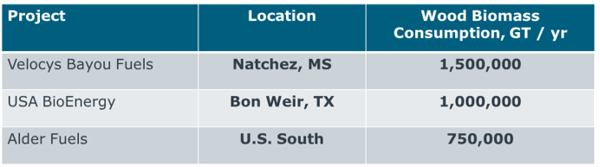

Despite the hurdles, wood-based SAF investments are flowing into the US South due to the region’s deep inventories of pine forest resources, which are overwhelmingly managed by private timberland owners who manage these resources as economic assets. This makes the South the lowest-cost forest economy in the US, and one of the most competitive in the world. Notable wood-biomass-to-fuels projects currently in development include:

BIG DATA + MODELS + EXPERTISE

Forest2Market has conducted hundreds of studies for bio-pathway producers, traditional forest products companies, government agencies, trade organizations and investors. Questions these clients seek to answer include:

- What are the market drivers of supply & demand?

- Where should we site the plant to assure long-term sustainability and affordability?

- What have prices done? What might they do? How could we manage?

In the next post on the topic of SAF, I will look at some of these projects in greater detail, as well as potential synergies that might provide fresh opportunities for traditional forest product companies operating in the region.

Matt Elhardt

Matt Elhardt